NFTs in Art Historical Context

Many people in the traditional art market are groping around in the dark, trying to divine how recent head-spinning developments in AI-generated art and so-called Non Fungible Assets (NFTs) will play out over time. Right now, the frenzy of speculative activity around these crypto innovations is akin to what would happen if you threw a fresh zebra carcass into a pride of lions.

Seasoned participants in the conventional art market understand its unique ecosystem, its specialist terminology, its sociological codes, its unconventional economic systems and pricing mechanisms, the importance of combining art historical knowledge with various kinds of analogue and digital information, and the importance of networking.

To those outside the perimeter fence, these codes and practices can seem arcane, opaque, elitist, and excluding of newcomers and neophytes. One suspects that many participants in the new crypto-ecosystem would echo the words of former baseball player turned NFT-artist Micah Johnson (right), who said of the traditional art world — “I don’t know how to navigate it.”

Micah Johnson

That sense of bewilderment is mirrored among traditional art world professionals who don’t know how to navigate Micah’s emerging crypto-environment.

But now the tables are turning and we’re witnessing a revolution unfolding at a dizzying velocity. Traditional market practitioners are looking with a mixture of dismay and trepidation at recent developments in the digital space that seem likely to overturn many of the established protocols on which the art market has relied for 250 years.

Barely two or three years ago, the words bitcoin and blockchain tended to meet with cavernous yawns from those outside the tech sector. And now everyone is wrestling with NFTs, crypto-art, smart contracts and tokenisation. Suddenly the barriers to understanding have switched and many legacy art market participants are struggling to orientate themselves to this new landscape.

Most of the discussion of late has been on the technological and financial structures underpinning the market for NFTs rather than on the art itself. A familiar refrain from critics of recent NFT events is: “It’s got nothing to do with art, it’s all about the money.” And yet it has often been said of the traditional art market, paraphrasing H.L.Mencken, “It’s not about the money, it’s about the money.”

Edmond de Belamy

While the price of the $69 million Beeple NFT understandably raised eyebrows, it was never the only game in town. There’s also a huge groundswell of enthusiasm for crypto-art at the lower price points, although whether any of it has any aesthetic merit seems to have been left out of the conversation. Art criticism has been in crisis for decades. Now it’s confronting a whole new challenge.

The Beeple sale at Christie’s, indeed even the price achieved for the AI-generated Portrait of Edmond Belamy (right) ought properly to be interpreted as attempts at a “Proof of Concept,” not only for the cryptocurrency platforms, but also for the ability of conventional auction houses to adapt to the new asset class.

Krista Kim, Mars House

It has been reported that the buyer of the NFT of Krista Kim’s virtual Mars House (left) has been approached by a couple requesting permission to hire the house for their wedding. With a little imagination one can see how some NFTs might have the potential to generate virtual derivatives that offer another profitable revenue stream to collectors. In my recent email exchange with Krista she told me of her involvement with the Superworld app, which she assures me, “will forever change the landscape of NFT art in the near future with 3D programmable NFTs minted on the Superworld platform, or uploaded from other platforms to experience in real time and space, through Artificial Reality.”

Speaking from a provenance research perspective, the recent blockchain-based developments are clearly of potentially positive benefit to artists and other market participants with regard to questions of uniqueness, scarcity, and thus authenticity, ownership history and the possibility of resale rights. Thus far this aspect has been largely confined to contemporary digital art. But what of historical material?

Recent digital innovations promise to offer a push towards the transparency and democratisation the art market has hitherto largely lacked. Only time will tell. As baseball legend Yogi Berra once noted, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

Many issues have yet to be interrogated in any depth, one of them being how crypto-art fits into a longer art historical tradition and whether it will evolve into a separate subset of the traditional art market or be somehow assimilated into its legacy structures. Might it even have the effect of marginalising previous hegemonic institutions and practices, or at any rate those that fail to adapt to the new environment?

In the meantime we are all free to speculate on the aesthetic dimension of the underlying asset and ask whether NFTs or cryptographically created art shares any characteristics with earlier art historical movements or represents an altogether different paradigm. With one or two notable exceptions, this art historical dimension seems to have been largely overlooked. Clearly it depends on the artist and the art, since crypto-art is not a bounded, stable category but a set of heterogenous practices within a new cultural mosaic of digital humanism and the social web. Much of what I’ve seen so far looks either arid and soulless — a product of an obsessive technophilia — or garish and infantile and seemingly designed to appeal purely on the basis of its digital genesis. The art market has always displayed herd-like behaviour, but the current stampede is on a whole new level.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Warrior

Seeking the possible roots of these changes, some market participants are already referring back to the rapid transformation of so-called street art, urban art or graffiti art into the established, blue-chip sector of the conventional primary and secondary markets. Jean-Michel Basquiat (left), Keith Haring, and Banksy have all been embraced in this way. While this neat teleological model is problematic on a number of levels,

the elevation of graffiti art from the street to the auction gallery does seem to foreshadow the current migration of crypto art from the Apple Mac desktop to the museum. Or just as likely, the transit from the desktop to the decentralised peer-to-peer network, bypassing the museum altogether, thereby giving a digital twist to André Malraux’s notion of the Museum without Walls.

But there may be other correspondences worth considering. If we rehearse for a moment the idea of a new community of fin-tech investors surfing in on the NFT craze, we may need to revisit the received wisdom (pace Marc Glimcher) that artists are the real disrupters. It now seems that role has shifted to the fin-tech and cryptocurrency sectors around which artists are rallying in numbers.

To many observers, digital art seems to be the new kid on the block, but in reality it constitutes a diverse range of practices that date back at least to the 1960s. What is new is the improved image software that allows for vastly expanded creative possibilities and the ability to instantly market the resulting work to a global audience in thrall to innovation, novelty and the new manifestations of the technological sublime.

Here might be a moment to put to bed the notion that established collectors of more traditional contemporary art are unlikely to respond to these new trends in image making. There is plenty of historical evidence that even the most challenging avant-garde tendencies have been embraced by adventurous, discriminating buyers drawn to experimentation and who identify with the risks involved in the creative act.

One thinks back to André Level’s Peau de L’Ours investment fund from 1904-14, one of the first structured investment vehicles to exploit the unrealised investment potential of the new works created by Picasso, Matisse, Van Dongen, Dufy and many of their contemporaries. So destabilising was the new wave of modernist, non-academic art at that time, that the British neoclassical painter John William Godward committed suicide, writing in his final note, “The world is not big enough for both myself and a Picasso.”

Godward found himself and his academic style of art decline in a very short space of time from a privileged insider status to a marginalised position as the new visual culture took hold. This is a lens through which we might analyse the current crop of crypto-artists — that is, as outsiders relative to the familiar names of the art historical canon.

I’m not seeking to draw formal comparisons between crypto-art and earlier examples of Modernist or Outsider Art, but rather to focus on how the practice of contemporary digital artists is occasionally seen (even by the artists themselves) as somehow marginal to the main art market event. Yet it was their very marginality that gave many of the earlier radical practices their cultural power, expressing an alternative vision of the world and forcing the art world’s gaze to momentarily shift from the centre to the periphery. That seems to be happening again today with the advent of crypto-art and NFTs.

The fascination with so-called ‘Tribal Art’ among Picasso and other members of the European avant-garde at the turn of the 19th-20th Century was another indication of how various forms of primitivism inspired many of the strains of disruption and disobedience that we now know as the Modernist movement. Almost contemporaneously, the shift of attention towards folk art, children’s art, the art of the insane, or that of incarcerated criminals, provided a further shot in the arm to a generation of artists of the inter-war period, notably Paul Klee, André Breton and the Surrealists, and of course Max Ernst and his Dada colleagues. Ernst had been an admirer and collector of the art of the mentally ill since before the First World War.

Jean Dubuffet

However, it was thanks to the stakhanovite efforts of Jean Dubuffet (right) in the 1940s, that many of these creations became enshrined under the rubric of Art Brut. Marginal they may have been at their inception, but the influence of many of these alternative voices endured, not least in Dubuffet’s own work. He has long been regarded as one of the most important figures in twentieth-century art, chiefly because he drew his coordinates from outside, and in opposition to, the dominant institutions of visual culture.

There is a constant tension in many of these alternative tendencies — and we would have to include later conceptual practices here too — between promoting the cultural importance of the art while resisting the siren call of the market. In almost every instance, however, the market wins out.

Bomarzo Giant

I ponder these “insider” and ”outsider” notions every time I visit the ‘Sacro Bosco’ Gardens of Bomarzo in Umbria, a park populated by numerous Mannerist sculptures by Simone Moschino (left) that later might have been considered under the rubric of ‘Outsider Art’. Most of the creations are in concrete, eschewing the more conventional standards of the time.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Vertumnus

The Milanese artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s portraits of the Habsburg Emperor Rudolf II in the 1590s (right) are generally seen as representative of Mannerism. But while Arcimboldo was no outsider, —being the favourite artist of Rudolf’s inner court circle — his work hints at a foretelling, avant la lettre, of later developments in Outsider Art.

Arcimboldo’s composite creations reverberate in the twentieth century in the work of the eccentric mosaicist and bric-a-brac dealer Pascal Désir Maisonneuve, who was among those whose work was conscripted into Jean Dubuffet’s groundbreaking Art Brut archive in the 1940s.

Pascal-Désir Maisonneuve

The work of artists like Maisonneuve (left) and his Art Brut contemporaries was not informed by an awareness of art history. Theirs is an introspective soliloquy brought forth in isolation and seemingly unmediated by external influence.

One is reluctant to dilate too much on the putative connections between so-called Outsider Art, Art Brut and the practices emerging from the contemporary crypto-art sector, but it already seems clear that many crypto-artists do see themselves as outsiders relative to the established art market.

With the tectonic plates shifting so radically, almost by the week, how long before these outsiders find themselves playing inside centre in the new art market? Some might argue that they already are.

One notable recent development was ‘The Encyclopaedic Palace,’ curated by Massimiliano Gioni for the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. The exhibition brought together untrained artists alongside works by recognised names in order to blur the boundaries between the work of professional artists and that of the self-taught.

In some ways this mirrored the aspirations of the Magicians de la Terre exhibition curated by Jean-Hubert Martin in Paris in 1989 which contributed to a different, but not unrelated aspect of the centre-periphery debate.

Primitivism Exhibition, (MoMA)

The exhibition blended Western with non-Western art as a corrective to what was seen as the Eurocentric tenor of William Rubin’s earlier exhibition, Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinities of the Tribal and the Modern at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1984 ( left).

In terms of critical reactions, it’s telling that when publicly exhibited in the late 1940s, Art Brut proved divisive, threatening to destabilise the Parisian art market. Some of the broadsides levelled at it at the time called it “a con,” “a hoax,” or, worse still, endangering art history and the whole aesthetic tradition. “Is it art?” asked one critic.

We hear a similar rhetoric by some established critics today in their dismissal of NFTs and crypto-art as a fad, a bubble, a contemporary recurrence of tulip mania.

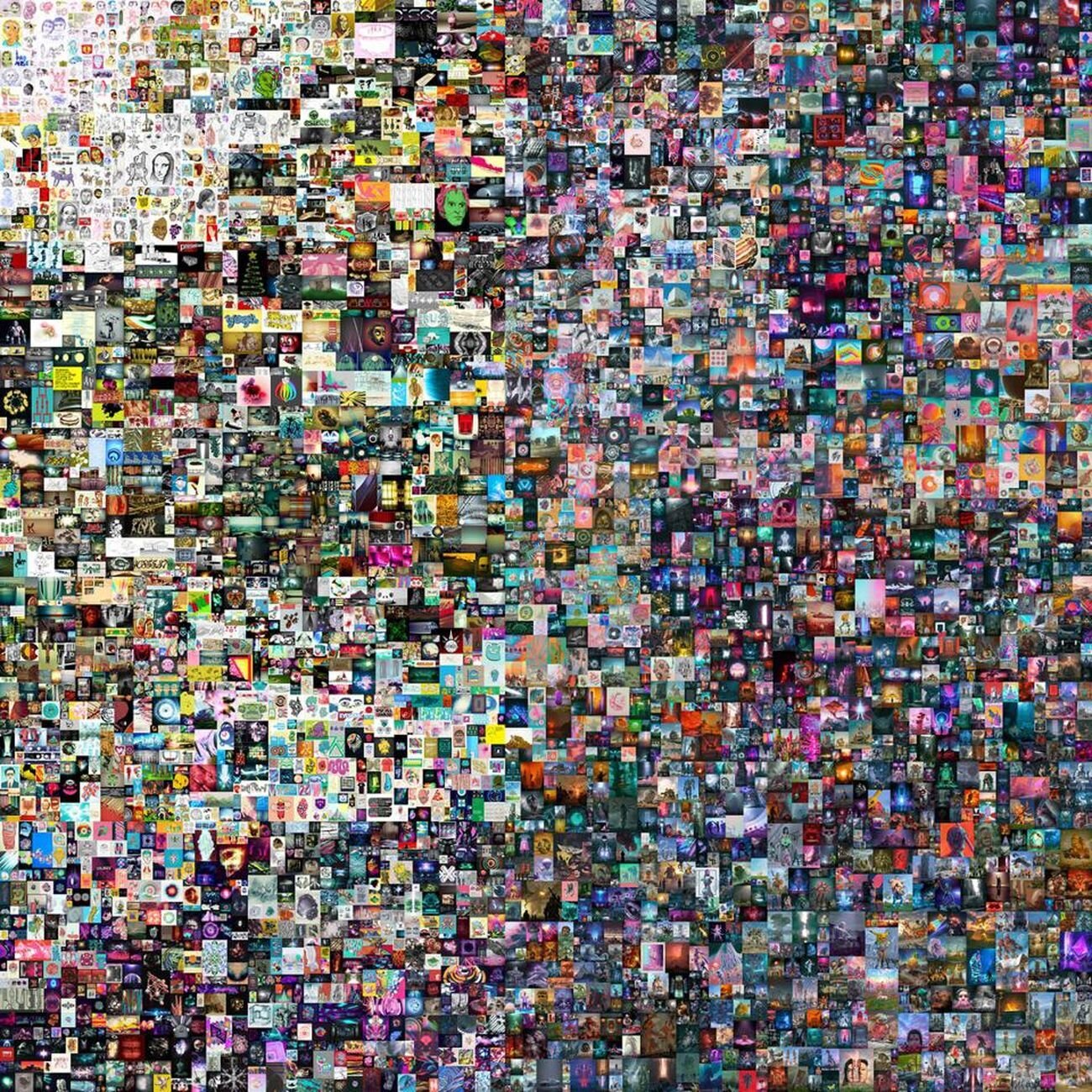

Beeple Everydays-The-First-5000-Days

In the 1940s the critic Jean Bouret said of Art Brut’s practitioners, “All of these people really amuse us, but the annoying thing is that none of them are worthy of the title artist.” We might contrast that with Mike Winkleman — aka Beeple’s — own response to being labelled an artist: “I don’t really like the term ‘artist’ because it sounds very pretentious and douchey, like I would never be like, ‘I’m an artist.’”

This attitude probably stems from Beeple’s self-identification as a professional graphic designer, but the success of his work in the new NFT art market confirms that the previously discreet boundaries between fine art, graphic design, computer-aided design and animation are no longer relevant to the emerging crypto art market. Anything can be an NFT; anyone can enter the NFT market. And that may be the problem.

At the fall of the hammer, Beeple has become something of a reluctant thought-leader in the new digitised metaverse. His dismissal of the term ‘artist’ seems to exemplify the prevailing attitude among some NFT creators towards the orthodox art world and its received nomenclature. Art Brut was also applauded by many as a welcome challenge to orthodoxy and an endorsement of the autonomy of the creators behind the work.

And that brings us to one other feature of the current crypto-art market that seems worth comparing to prior historical moments. As we’e mentioned, digital art is now at least half a century old, but the use of technology by artists goes back even further. We could start with Leonardo, of course, and proceed through Vermeer’s use of a camera obscura, to the disruptive impact of photography on the art world in the 19th century. Yet in the twentieth century can be found numerous even more relevant examples of artists using science and technology to expand their creative practice. One obvious point of departure might be Duchamp’s and Man Ray’s joint experiments with motorised optics, as in, for example, Duchamp’s Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Objects in Motion) of 1920.

Tinguely, Parade of Machines

That trajectory continued in the post-war period with Swiss artist Jean Tinguely’s self-annihilating meta-mechanical machines (one of his ludic scrap metal installations from the early 1960s shown left). Later artists picking up on this existentialist vector of self-annihilation include John Baldessari who in 1970 cremated his entire ‘body of work’ made between 1953 and 1966.

More recently, the British artist Michael Landy created his Break Down project in which he spent two-weeks in 2001 publicly pulverising all his worldly possessions at a department store on London’s Oxford Street as a comment on rampant consumerism. More recently we’d have to include in this self-destructive category Banksy’s shredding of his Girl with Balloon and his later burning of the work Morons. The film of the immolation was then sold as an NFT.

Unlike the self-destructive works of Tinguely, Baldessari and their generation, whose work reflected the anxiety of the Cold War era, these more recent contemporary examples may come across to some as opportunistic, sensationalist and exploitative, but have also been read as a critical commentary on the bloated art market from which they nevertheless draw significant financial benefit.

Following the success of Tinguely’s mechanised Study No.2 for an End of the World, a self-annihilating piece staged in the Las Vegas desert in 1962, he envisioned the future in a way that now seems strikingly clairvoyant, and I quote: “…we’re living in an age when the wildest fantasies become daily truths. Anything is possible. Dematerialisation, for example, that will enable people to travel by becoming sound waves or something. Why not? I’m trying to meet the scientist a little beyond the frontier of the possible, even to get there a little ahead of him.” (Quoted in Jack Berman, Beyond Modern Sculpture, Allen Lane, London 1968, p245)

Piet Mondrian, Noll

Tinguely’s reference to dematerialisation coincides with the use of that term in a more nuanced context by Lucy Lippard in her book Six Years. Her writing plots a critical history of the dematerialisation of the art object from 1966 to 1972 analysing a range of disruptive intellectual tendencies that came to be labelled Conceptual Art. And now that concept of dematerialisation has come full circle with Christie’s sale of a jpeg as an NFT.

Around the same time Tinguely and Lucy Lippard were writing, another development was emerging from computer science.

In 1966, A. Michael Noll of the Bell Telephone Laboratories in New Jersey used a digital computer and microfilm plotter to produce a semi-random picture (above left) similar in composition to Piet Mondrian’s black and white painting of 1917, Composition with Lines. A survey of 100 subjects invited to view both images revealed that only 28 percent of respondents were able to correctly identify the computer-generated picture, while 59 percent preferred the computer-generated image. This was one of the first experiments into how the algorithmic functions used in computer technology helped stimulate an aesthetics of digital abstraction. Noll exhibited some of his work in a group show entitled Computer-Generated Pictures at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York in 1965.

Robert Rauschenberg, Nine Evenings

The American artist Robert Rauschenberg is also notable for his engagement with various forms of science and technology. In 1966, around the time of Noll’s show at the Howard Wise Gallery, Rauschenberg was forming E.A.T. (Experiments in Art & Technology) with the engineers Billy Klüver, Fred Waldhauer and the artist Robert Whitman. Klüver and Waldhauer were also from Bell Telephone Labs. The aim of the project was to build bridges between artists and engineers. It resulted in a collaboration the outcome of which was complex and chaotic, but which was to have a lasting impact.

The coming together of the two cultures of art and science on a shared endeavour — namely the seminal performance series at the Seventh Regiment Armory entitled 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering in 1966 — stimulated a shift in artists’ attitudes towards science and engineering and in scientists’ and engineers’ engagement with visual and performance art. And we should also genuflect here towards members of the Fluxus group who were using technological innovations at around the same time. One thinks of Nam June Paik’s discovery of the Sony Portapak portable video camera in 1965, to name one example of many.

And once again this is not to suggest that we map the creative outcomes of these projects onto the crypto-art we’re seeing today but rather to point to yet another instance of how seemingly separate disciplines when brought together in a spirit of creative cooperation have the capacity to, as Rauschenberg put it, “make work that could not exist otherwise.”

The conjunction we’re witnessing in today’s environment — between crypto-art, fin-tech, blockchain and network engineering — has the potential to bring about a deep structural change in the art ecosystem, perhaps even to remake the art market in a way that could not have been achieved otherwise, to borrow Rauschenberg’s gloss.

Needless to say, not everyone today welcomes the prospect of such a change. But as Billy Klüver said on the opening night of the Nine Evenings performance, “There are three elements fighting here — the artists, the engineers, and the audience. These three will have to come to some resolution.” We can hear Klüver’s words echoed by NFT artist Krista Kim, who has written, “Collaboration, co-creation and dialogue with engineers and technology specialists is key to the Techism movement, because we are in a transition phase between the institutionalised ‘painting & sculpture’ tradition of artistic expression, into digital.”

By now you might be concluding that there are few if any direct precedents for what we’re witnessing today, or perhaps I’ve merely failed to suggest more appropriate comparisons from the long historical archive. That might be because the revolution we’re witnessing is occurring on three or four fronts at the same time — in the financial technology precinct, in art investment circles, in the creative practices of crypto-artists and, arguably most critically, in the challenges to the established art market institutions, which are now being exposed for their insularity, élitism, opacity and relative lack of regulation.

Notwithstanding these characteristics of the legacy market, one cannot help feeling a certain background anxiety and apprehension at the destabilising of the foundations on which the traditional art market has relied since the second half of the eighteenth century. But let’s keep some perspective here. Some of us witnessed at close quarters the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s/early 2000s and the subsequent roadkill scattered over the investment super-highway.

The inner sanctum of traditional art trading, which benefits largely from what economists call network externalities, will surely endure in some form as a sector reliant on established relationships and mutual trust. While there’s no question that the writing is on the gallery wall, the recent Nostradamus-like forecasts of the legacy art trade’s slow descent into ancestral decrepitude may be somewhat premature. We’re simply entering a new era and the future is what we choose to make of it.

Don’t underestimate the capacity of the primary and secondary market players to respond creatively to the new landscape. The rapidity of the response by the auction houses, art fairs and primary galleries to the Covid pandemic was evidence of how technology is no longer the sole preserve of Silicon Valley but is now part of the toolkit of every agile, forward-thinking art business model.

Even the traditional art trade is capable of adapting to severe economic constraints with impressive speed. The future will doubtless be a hybrid between the old and the spanking new, which is nothing more than a response to a growing global market of networked millennials excited by the possibilities of art in the digitally expanded field. But while the market is adapting quickly, the NFT and cryptocurrency sectors need to respond even more urgently to the destructive ecological impact of bitcoin mining.

Seth Siegelaub, ARRTASA

Finally, how might Seth Siegelaub might have viewed these recent developments in NFTs and the blockchain? The ability of smart contracts to be written in such a way as to ensure a percentage return to the artist in any future transaction (something Beeple has already handsomely benefited from) sounds like the digital realisation of Siegelaub’s Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement of 1971 (above). This was a conceptual project undertaken with the lawyer Robert Pojansky that sought to enshrine the moral rights of the artist in any secondary art sale contract.

Hanging above the current changes reverberating through the market are a host of legal questions concerning copyright, appropriation, the future of connoisseurship and forensic science, all of which will continue to be critical issues in the market moving forward, in whatever form it takes.

Some of those disciplines and procedures may in time be replaced by technological alternatives. But we will still have an existing archive of historical objects circulating in the conventional art market that call for the kind of aesthetic instinct, specialist art historical knowledge, archival research and expertise that digital technology is yet to replace with a viable alternative, notwithstanding the advances in AI.

Nevertheless, if the current trends continue with the intensity we’ve witnessed of late, a newly democratised art market may no longer be just another libertarian pipe dream, but a genuine prospect. As the theoretical physicist Richard Feynman once said, “There was a time in the evolution of everything that works, when it didn’t work.”