Connecting the Dots: The Use of Dealers' Records in Provenance Research

Have you ever wondered how provenance researchers piece together an object's past? Like a police investigation, establishing provenance revolves around connecting the dots. Yet, unlike a crime scene, the evidence is dispersed across a global network of archives and libraries. Within these holding institutions, lie the records of art dealers, a sought-after tool in the provenance researcher’s arsenal.

A considerable number of artworks have likely transitioned through the hands of dealers, leaving behind a trace in their sales catalogues, inventories, invoices, and correspondence. These records offer valuable insights into their transactions, allowing researchers to identify key moments and individuals involved in the sale or transfer of artworks. Among these records, stock books stand out as a treasure trove of information, often containing details such as acquisition dates, seller information, artwork dimensions, purchaser names, sale dates, and even acquisition and selling prices.

It is important to note that delving into dealers' records can, at times, be a daunting task. The availability and integrity of these archives can widely differ, with some being lost or damaged over time, adding an extra layer of complexity to the research. Additionally, not all dealers historically maintained meticulous documentation, especially during periods when record-keeping practices were less standardized. However, in recent years, institutions have acknowledged the significance of these records and have taken proactive steps to collect and preserve them. Furthermore, technological advancements have made it possible to access archives online, a convenient addition to the conventional in-person visits to the reading rooms. The Archives of American Art has collected the archives of The American Art Association and various other American dealers such as Jacques and Germain Seligmann or Leo Castelli, while in London, The National Gallery has acquired and digitized the records of the London dealer Agnew's. In 1965, The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute bought the documentation from the library of the Duveen Brothers. Later, the collection was transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and eventually donated to the Getty Research Institute in 1996. The Duveen Brothers played a crucial role in forming private fine and decorative art collections that eventually became renowned museums like the National Gallery of Art, the Huntington Art Collections, and the Frick Collection.

The Getty Research Institute is one of the world’s largest repository of dealers’ archives. Its collection originated with the acquisition in 1989 of the Dieterle family records of French art galleries, which encompasses the papers of eight esteemed 19th century art dealers, including Goupil, Boussod & Valadon, Bague et cie, Georges Petit, Allard et Noel, Tedesco, Arnold et Tripp. The Getty Research Institute (GRI), at the forefront of utilizing technology to advance provenance research has taken on the monumental task of digitizing the stock books of two prominent art dealers, Goupil & cie (Boussod, Valadon & cie) and Knoedler & co - acquired in 2012.

Between 1846 and 1919 Goupil & Cie dominated the French art market, showcasing the works of esteemed 19th-century artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and the influential figures of the Barbizon School. With galleries in Paris, Berlin, Brussels, The Hague, and London, their reach extended far and wide. They even had agents and clients in the Ottoman Empire and Australia. In America, Goupil established a gallery in New York in 1848, which they later sold to their manager, Michael Knoedler, in 1857 while maintaining close ties. This collaboration proved highly successful, and upon its closure in 2011, Knoedler & Co stood as one of the oldest and most prestigious galleries in New York. Goupil and Knoedler played crucial roles in shaping private American collections, in addition to making contributions to public collections such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Walters Art Museum.

Both Goupil and Knoedler’s archives show meticulous record-keeping practices. For years, however, these records were not widely accessible for study, with the Knoedler records only available at the gallery's New York office and the Goupil archives limited to a select few researchers in France. Beyond the mere digitization of the stock books, the Getty Research Institute has gone a step further by converting the original handwritten records into two searchable, interconnected, and sortable databases. What was once a privilege limited to a select few is now within reach of anyone with an internet connection.

As part of my doctoral research, I launched my own Goupil & Cie Stock Books database project with the aim of analyzing the globalization of Goupil's gallery network from 1846 to 1884. Following this, the Getty Provenance Index opted to broaden the project's scope by extending the chronology up to 1919, digitizing the books and providing public access to the resulting database. It took me over a year and a half to decipher the handwritten stock books and manually enter the 31,000 records but the collaboration resulted in the first institutional online dealer database. Today, it provides expanded access to information on artists, buyers, prices, and has opened new possibilities, especially with the subsequent incorporation of the Knoedler & Co database, spanning from the 1850s to 1971.

Even now, as a researcher and appraiser, I rely on the dealers’ databases almost daily for my clients and personal projects. Recently, I have been involved with the development of the catalogue raisonné of Jules Breton, the 19th-century painter renowned for his depictions of peasants. Working alongside Annette Bourrut Lacouture to bring her lifelong project to fruition has been an exceptionally fulfilling journey. Utilizing databases and digitized archives, which did not exist when Annette started her work some 40 years ago, we successfully addressed gaps, tracked down, and unearthed previously unknown works. Only naturally, I investigated the Goupil and Knoedler records for clues. Due to their influential positions on the art market during the artist’s lifetime, both dealers handled a significant number of works by Jules Breton. Out of his approximately corpus of 800 paintings, 92 went through Goupil, 83 through Knoedler and 33 through both dealers.

Two years ago, hidden in the depths of Knoedler's photo archives (accessible in person in the Special Collection reading Room of the GRI), laid a mystery painting representing a harvester (Glaneuse) that we knew nothing about.

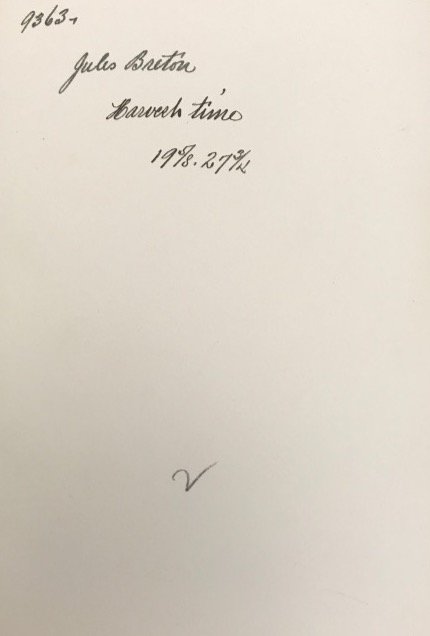

At the back of the photograph, there was the title, an inventory number and the dimensions.

The following image shows the complexity of Knoedler’s handwriting and record keeping. While searching for this particular painting in the actual books would have taken an hour, only 5 minutes were necessary to find a match in the database.

And the way the same entry appears in the stock books:

Screenshot of the Knoedler GRI database for La Glaneuse.

The next step was to pull the thread and follow the clues left by Knoedler, such as the origin of the painting and his buyer. Knoedler purchased the work at an auction organized by the American Art Association in 1901. A month later, they sold it to a certain William E. Spaulding, from Boston with a mark-up of $1500. Our catalogue entry for this work is as follow:

Establishing provenance is about connecting the dots and following the trail left by the dealers in their stock books. Tricoteuse sous un arbre, is another work discovered via the use of the dealers stock books and the Knoedler photo archives.

In the photo bank, I discovered a Tricoteuse (Peasant knitting), which is probably the version Jules Breton had prepared for the 1871 Salon. The Salon however never happened that year because of the Franco-Prussian war, but Breton sold the smaller study that is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to Catharine Lorillard Wolfe through Goupil in 1873. Lorillard Wolfe eventually bequeathed the work to the Met in 1887.

(https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435774)

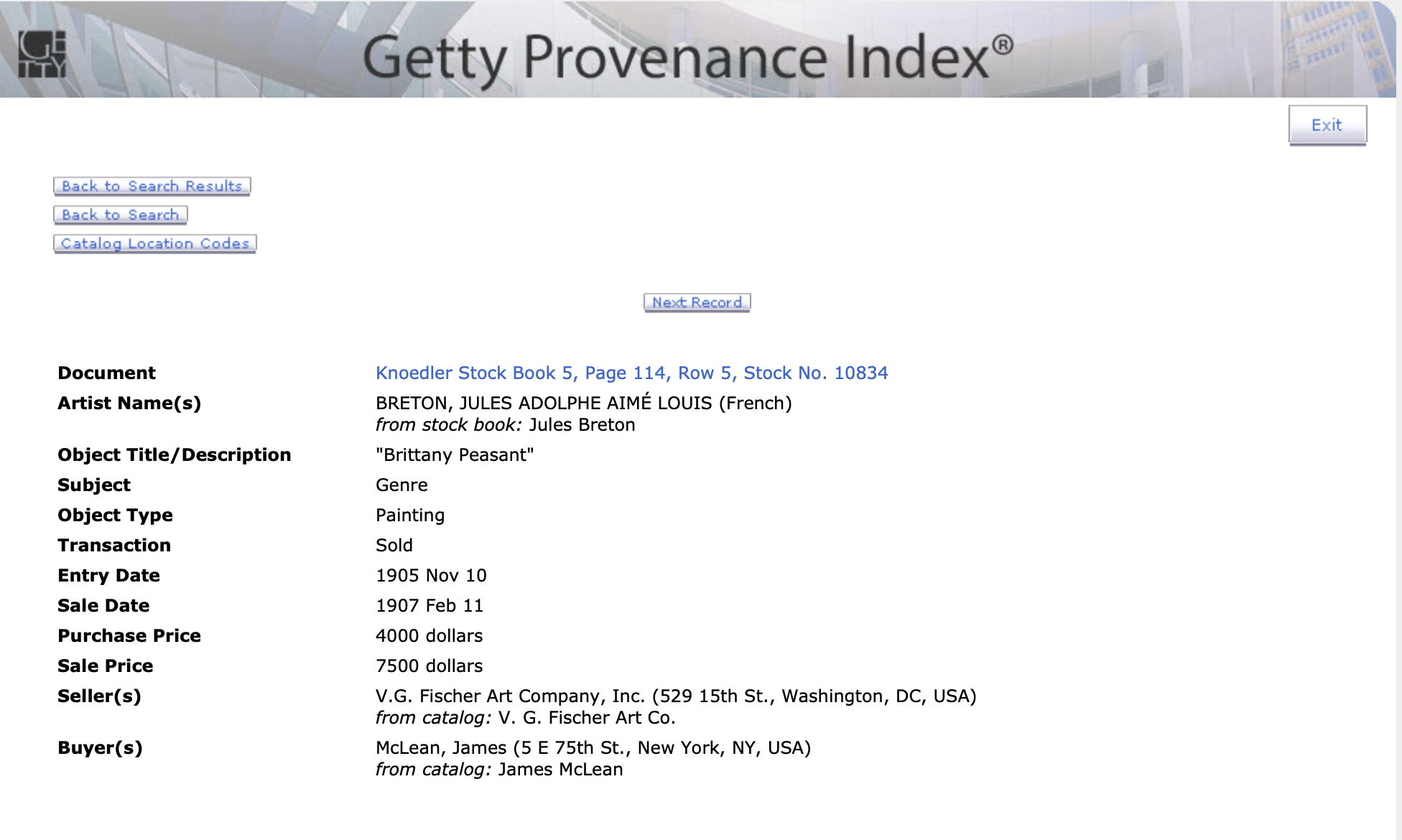

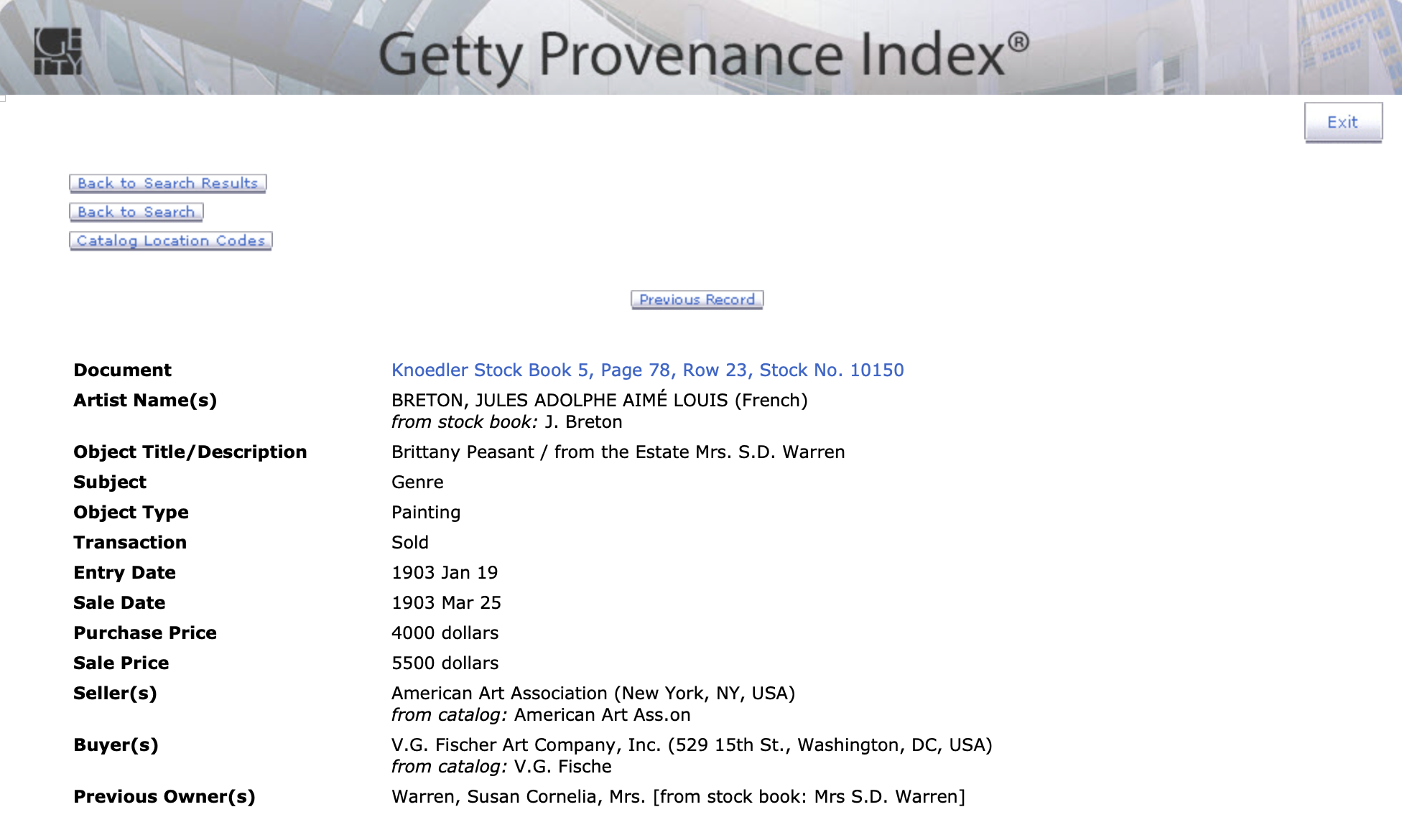

Once again, I consulted the Knoedler database searching for the records of transfer. It turns out Knoedler handled the painting twice, in 1903 and 1905. The first time, they bought it at auction via The American Art Association (sale of Susan Cornelia Warren) and then sold it to V. G. Fisher Art Company. The second time, 2 years later, was probably a return from Fisher Art Company. The painting remained in Knoedler’s inventory for almost 2 years until James Mc Lean acquired it in 1907.

To ensure accuracy, I cross-referenced the artwork with the Goupil database and found a match. Goupil had initially acquired the painting in 1873 from Hector Brame, a fellow Parisian dealer, and subsequently sold it to the British dealer Everard. It is probable that Samuel Dennis Warren, the influential Boston paper magnate and art collector, acquired the artwork from Everard.

Our final entry reads as follow:

Connecting the dots of La Tricoteuse was a combination of luck, patience and instinct. Despite losing track of the painting after 1907, the reemergence of La Tricoteuse on the market will eventually provide a fresh opportunity to resume the investigation into its recent whereabouts. Provenance research, while inherently complex and reliant on historical facts and period knowledge, is also greatly influenced by the availability and accessibility of archives, as demonstrated in the examples highlighted in the Jules Breton Catalogue raisonné.